8. Profiling¶

GHC comes with a time and space profiling system, so that you can answer questions like “why is my program so slow?”, or “why is my program using so much memory?”. We’ll start by describing how to do time profiling.

Time profiling a program is a three-step process:

Re-compile your program for profiling with the

-profoption, and probably one of the options for adding automatic annotations:-fprof-lateis the recommended option.Having compiled the program for profiling, you now need to run it to generate the profile. For example, a simple time profile can be generated by running the program with

+RTS -p(see-p), which generates a file namedprog.profwhere ⟨prog⟩ is the name of your program (without the.exeextension, if you are on Windows).There are many different kinds of profile that can be generated, selected by different RTS options. We will be describing the various kinds of profile throughout the rest of this chapter. Some profiles require further processing using additional tools after running the program.

Examine the generated profiling information, use the information to optimise your program, and repeat as necessary.

The time profiler measures the CPU time taken by the Haskell code in your application. In particular time taken by safe foreign calls is not tracked by the profiler (see Profiling and foreign calls).

8.1. Cost centres and cost-centre stacks¶

GHC’s profiling system assigns costs to cost centres. A cost is simply the time or space (memory) required to evaluate an expression. Cost centres are program annotations around expressions; all costs incurred by the annotated expression are assigned to the enclosing cost centre. Furthermore, GHC will remember the stack of enclosing cost centres for any given expression at run-time and generate a call-tree of cost attributions.

Let’s take a look at an example:

main = print (fib 30)

fib n = if n < 2 then 1 else fib (n-1) + fib (n-2)

Compile and run this program as follows:

$ ghc -prof -fprof-auto -rtsopts Main.hs

$ ./Main +RTS -p

121393

$

When a GHC-compiled program is run with the -p RTS option, it

generates a file called prog.prof. In this case, the file will contain

something like this:

Wed Oct 12 16:14 2011 Time and Allocation Profiling Report (Final)

Main +RTS -p -RTS

total time = 0.68 secs (34 ticks @ 20 ms)

total alloc = 204,677,844 bytes (excludes profiling overheads)

COST CENTRE MODULE %time %alloc

fib Main 100.0 100.0

individual inherited

COST CENTRE MODULE no. entries %time %alloc %time %alloc

MAIN MAIN 102 0 0.0 0.0 100.0 100.0

CAF GHC.IO.Handle.FD 128 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF GHC.IO.Encoding.Iconv 120 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF GHC.Conc.Signal 110 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF Main 108 0 0.0 0.0 100.0 100.0

main Main 204 1 0.0 0.0 100.0 100.0

fib Main 205 2692537 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

The first part of the file gives the program name and options, and the total time and total memory allocation measured during the run of the program (note that the total memory allocation figure isn’t the same as the amount of live memory needed by the program at any one time; the latter can be determined using heap profiling, which we will describe later in Profiling memory usage).

The second part of the file is a break-down by cost centre of the most

costly functions in the program. In this case, there was only one

significant function in the program, namely fib, and it was

responsible for 100% of both the time and allocation costs of the

program.

The third and final section of the file gives a profile break-down by

cost-centre stack. This is roughly a call-tree profile of the program.

In the example above, it is clear that the costly call to fib came

from main.

The time and allocation incurred by a given part of the program is displayed in two ways: “individual”, which are the costs incurred by the code covered by this cost centre stack alone, and “inherited”, which includes the costs incurred by all the children of this node.

The usefulness of cost-centre stacks is better demonstrated by modifying the example slightly:

main = print (f 30 + g 30)

where

f n = fib n

g n = fib (n `div` 2)

fib n = if n < 2 then 1 else fib (n-1) + fib (n-2)

Compile and run this program as before, and take a look at the new profiling results:

COST CENTRE MODULE no. entries %time %alloc %time %alloc

MAIN MAIN 102 0 0.0 0.0 100.0 100.0

CAF GHC.IO.Handle.FD 128 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF GHC.IO.Encoding.Iconv 120 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF GHC.Conc.Signal 110 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF Main 108 0 0.0 0.0 100.0 100.0

main Main 204 1 0.0 0.0 100.0 100.0

main.g Main 207 1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.1

fib Main 208 1973 0.0 0.1 0.0 0.1

main.f Main 205 1 0.0 0.0 100.0 99.9

fib Main 206 2692537 100.0 99.9 100.0 99.9

Now although we had two calls to fib in the program, it is

immediately clear that it was the call from f which took all the

time. The functions f and g which are defined in the where

clause in main are given their own cost centres, main.f and

main.g respectively.

The actual meaning of the various columns in the output is:

The number of times this particular point in the call tree was entered.

The percentage of the total run time of the program spent at this point in the call tree.

The percentage of the total memory allocations (excluding profiling overheads) of the program made by this call.

The percentage of the total run time of the program spent below this point in the call tree.

The percentage of the total memory allocations (excluding profiling overheads) of the program made by this call and all of its sub-calls.

In addition you can use the -P RTS option to get the

following additional information:

ticksThe raw number of time “ticks” which were attributed to this cost-centre; from this, we get the

%timefigure mentioned above.bytesNumber of bytes allocated in the heap while in this cost-centre; again, this is the raw number from which we get the

%allocfigure mentioned above.

What about recursive functions, and mutually recursive groups of functions? Where are the costs attributed? Well, although GHC does keep information about which groups of functions called each other recursively, this information isn’t displayed in the basic time and allocation profile, instead the call-graph is flattened into a tree as follows: a call to a function that occurs elsewhere on the current stack does not push another entry on the stack, instead the costs for this call are aggregated into the caller [2].

8.1.1. Inserting cost centres by hand¶

Cost centres are just program annotations. When you say -fprof-auto

to the compiler, it automatically inserts a cost centre annotation

around every binding not marked INLINE in your program, but you are

entirely free to add cost centre annotations yourself. Be careful adding too many

cost-centre annotations as the optimiser is careful to not move them around or

remove them, which can severly affect how your program is optimised and hence the

runtime performance!

The syntax of a cost centre annotation for expressions is

{-# SCC "name" #-} <expression>

where "name" is an arbitrary string, that will become the name of

your cost centre as it appears in the profiling output, and

<expression> is any Haskell expression. An SCC annotation extends as

far to the right as possible when parsing, having the same precedence as lambda

abstractions, let expressions, and conditionals. Additionally, an annotation

may not appear in a position where it would change the grouping of

subexpressions:

a = 1 / 2 / 2 -- accepted (a=0.25)

b = 1 / {-# SCC "name" #-} 2 / 2 -- rejected (instead of b=1.0)

This restriction is required to maintain the property that inserting a pragma, just like inserting a comment, does not have unintended effects on the semantics of the program, in accordance with GHC Proposal #176.

SCC stands for “Set Cost Centre”. The double quotes can be omitted if name

is a Haskell identifier starting with a lowercase letter, for example:

{-# SCC id #-} <expression>

Cost centre annotations can also appear in the top-level or in a declaration context. In that case you need to pass a function name defined in the same module or scope with the annotation. Example:

f x y = ...

where

g z = ...

{-# SCC g #-}

{-# SCC f #-}

If you want to give a cost centre different name than the function name, you can pass a string to the annotation

f x y = ...

{-# SCC f "cost_centre_name" #-}

Here is an example of a program with a couple of SCCs:

main :: IO ()

main = do let xs = [1..1000000]

let ys = [1..2000000]

print $ {-# SCC last_xs #-} last xs

print $ {-# SCC last_init_xs #-} last (init xs)

print $ {-# SCC last_ys #-} last ys

print $ {-# SCC last_init_ys #-} last (init ys)

which gives this profile when run:

COST CENTRE MODULE no. entries %time %alloc %time %alloc

MAIN MAIN 102 0 0.0 0.0 100.0 100.0

CAF GHC.IO.Handle.FD 130 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF GHC.IO.Encoding.Iconv 122 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF GHC.Conc.Signal 111 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

CAF Main 108 0 0.0 0.0 100.0 100.0

main Main 204 1 0.0 0.0 100.0 100.0

last_init_ys Main 210 1 25.0 27.4 25.0 27.4

main.ys Main 209 1 25.0 39.2 25.0 39.2

last_ys Main 208 1 12.5 0.0 12.5 0.0

last_init_xs Main 207 1 12.5 13.7 12.5 13.7

main.xs Main 206 1 18.8 19.6 18.8 19.6

last_xs Main 205 1 6.2 0.0 6.2 0.0

8.1.2. Rules for attributing costs¶

While running a program with profiling turned on, GHC maintains a cost-centre stack behind the scenes, and attributes any costs (memory allocation and time) to whatever the current cost-centre stack is at the time the cost is incurred.

The mechanism is simple: whenever the program evaluates an expression

with an SCC annotation, {-# SCC c -#} E, the cost centre c is

pushed on the current stack, and the entry count for this stack is

incremented by one. The stack also sometimes has to be saved and

restored; in particular when the program creates a thunk (a lazy

suspension), the current cost-centre stack is stored in the thunk, and

restored when the thunk is evaluated. In this way, the cost-centre stack

is independent of the actual evaluation order used by GHC at runtime.

At a function call, GHC takes the stack stored in the function being called (which for a top-level function will be empty), and appends it to the current stack, ignoring any prefix that is identical to a prefix of the current stack.

We mentioned earlier that lazy computations, i.e. thunks, capture the

current stack when they are created, and restore this stack when they

are evaluated. What about top-level thunks? They are “created” when the

program is compiled, so what stack should we give them? The technical

name for a top-level thunk is a CAF (“Constant Applicative Form”). GHC

assigns every CAF in a module a stack consisting of the single cost

centre M.CAF, where M is the name of the module. It is also

possible to give each CAF a different stack, using the option

-fprof-cafs. This is especially useful when

compiling with -ffull-laziness (as is default with -O

and higher), as constants in function bodies will be lifted to the top-level

and become CAFs. You will probably need to consult the Core

(-ddump-simpl) in order to determine what these CAFs correspond to.

8.2. Profiling and foreign calls¶

Simply put, the profiler includes time spent in unsafe foreign

calls but ignores time taken in safe foreign calls. For example, time spent blocked on IO

operations (e.g. getLine) is not accounted for in the profile as getLine is implemented

using a safe foreign call.

The profiler estimates CPU time, for Haskell threads within the program only. In particular, time “taken” by the program in blocking safe foreign calls is not accounted for in time profiles. The runtime has the notion of a virtual processor which is known as a “capability”. Haskell threads are run on capabilities, and the profiler samples the capabilities in order to determine what is being executed at a certain time. When a safe foreign call is executed, it’s run outside the context of a capability; hence the sampling does not account for the time taken. Whilst the safe call is executed, other Haskell threads are free to run on the capability, and their cost will be attributed to the profiler. When the safe call is finished, the blocked, descheduled thread can be resumed and rescheduled.

However, the time taken by blocking on unsafe foreign calls is accounted for in the profile. This happens because unsafe foreign calls are executed by the same capability their calling Haskell thread is running on. Therefore, an unsafe foreign call will block the entire capability whilst it is running, and any time the capability is sampled the “cost” of the foreign call will be attributed to the calling cost-centre stack.

However, do note that you are not supposed to use unsafe foreign calls for any operations which do block! Do not be tempted to replace your safe foreign calls with unsafe calls just so they appear in the profile. This prevents GC from happening until the foreign call returns, which can be catastrophic for performance.

8.3. Compiler options for profiling¶

- -prof¶

To make use of the profiling system all modules must be compiled and linked with the

-profoption. AnySCCannotations you’ve put in your source will spring to life.Without a

-profoption, yourSCCs are ignored; so you can compileSCC-laden code without changing it.

- -fno-prof-count-entries¶

Tells GHC not to collect information about how often functions are entered at runtime (the “entries” column of the time profile), for this module. This tends to make the profiled code run faster, and hence closer to the speed of the unprofiled code, because GHC is able to optimise more aggressively if it doesn’t have to maintain correct entry counts. This option can be useful if you aren’t interested in the entry counts (for example, if you only intend to do heap profiling).

There are a few other profiling-related compilation options. Use them

in addition to -prof. These do not have to be used consistently

for all modules in a program.

8.3.1. Automatically placing cost-centres¶

GHC has a number of flags for automatically inserting cost-centres into the compiled program. Use these options carefully because inserting too many cost-centres in the wrong places will mean the optimiser will be less effective and the runtime behaviour of your profiled program will be different to that of the unprofiled one.

- -fprof-callers=⟨name⟩¶

Automatically enclose all occurrences of the named function in an

SCC. Note that these cost-centres are added late in compilation (after simplification) and consequently the names may be slightly different than they appear in the source program (e.g. a call tofmay inlined with its wrapper, resulting in an occurrence of its worker,$wf).In addition to plain module-qualified names (e.g.

GHC.Base.map), ⟨name⟩ also accepts a small globbing language using*as a wildcard symbol:pattern := <module> '.' <identifier> module := '*' | <Haskell module name> identifier := <ident_char> identFor instance, the following are all valid patterns:

Data.List.map*.map*.parse**.<\*>

The

*character can be used literally by escaping (e.g.\*).

- -fprof-auto¶

All bindings not marked

INLINE, whether exported or not, top level or nested, will be given automaticSCCannotations. Functions markedINLINEmust be given a cost centre manually.

- -fprof-auto-top¶

GHC will automatically add

SCCannotations for all top-level bindings not markedINLINE. If you want a cost centre on anINLINEfunction, you have to add it manually.

- -fprof-auto-exported¶

GHC will automatically add

SCCannotations for all exported functions not markedINLINE. If you want a cost centre on anINLINEfunction, you have to add it manually.

- -fprof-auto-calls¶

Adds an automatic

SCCannotation to all call sites. This is particularly useful when using profiling for the purposes of generating stack traces; see the function Debug.Trace.traceShow, or the-xcRTS flag (RTS options for Haskell program coverage) for more details.

- -fprof-late¶

- Since:

9.4.1

Adds an automatic

SCCannotation to all top level bindings which might perform work. This is done late in the compilation pipeline after the optimizer has run and unfoldings have been created. This means these cost centres will not interfere with core-level optimizations and the resulting profile will be closer to the performance profile of an optimized non-profiled executable.While the results of this are generally informative, some of the compiler internal names will leak into the profile. Further if a function is inlined into a use site it’s costs will be counted against the caller’s cost center.

For example if we have this code:

{-# INLINE mysum #-} mysum = sum main = print $ mysum [1..9999999]

Then

mysumwill not show up in the profile since it will be inlined into main and therefore it’s associated costs will be attributed to mains implicit cost centre.

- -fprof-late-inline¶

- Since:

9.4.1

Adds an automatic

SCCannotation to all top level bindings late in the core pipeline after the optimizer has run. This is the same as-fprof-lateexcept that cost centers are included in some unfoldings.The result of which is that cost centers can inhibit core optimizations to some degree at use sites after inlining. Further there can be significant overhead from cost centres added to small functions if they are inlined often.

You can try this mode if

-fprof-lateresults in a profile that’s too hard to interpret.

- -fprof-late-overloaded¶

- Since:

9.10.1

Adds an automatic

SCCannotation to all overloaded top level bindings late in the compilation pipeline after the optimizer has run and unfoldings have been created. This means these cost centres will not interfere with core-level optimizations and the resulting profile will be closer to the performance profile of an optimized non-profiled executable.This flag can help determine which top level bindings encountered during a program’s execution are still overloaded after inlining and specialization.

- -fprof-late-overloaded-calls¶

- Since:

9.10.1

Adds an automatic

SCCannotation to all call sites that include dictionary arguments late in the compilation pipeline after the optimizer has run and unfoldings have been created. This means these cost centres will not interfere with core-level optimizations and the resulting profile will be closer to the performance profile of an optimized non-profiled executable.This flag is potentially more useful than

-fprof-late-overloadedsince it will also addSCCannotations to call sites of imported overloaded functions.Some overloaded calls may not be annotated, specifically in cases where the optimizer turns an overloaded function into a join point. Calls to such functions will not be wrapped in

SCCannotations, since it would make them non-tail calls, which is a requirement for join points. Instead,SCCannotations are added around the body of overloaded join variables and given distinct names (join-rhs-<var>) to avoid confusion.

- -fprof-cafs¶

The costs of all CAFs in a module are usually attributed to one “big” CAF cost-centre. With this option, all CAFs get their own cost-centre. An “if all else fails” option…

- -fprof-manual¶

- Default:

on

Process (or ignore) manual

SCCannotations. Can be helpful to ignore annotations from libraries which are not desired.

- -auto-all¶

Deprecated alias for

-fprof-auto

- -auto¶

Deprecated alias for

-fprof-auto-exported

- -caf-all¶

Deprecated alias for

-fprof-cafs

- -no-auto-all¶

Deprecated alias for

-fno-prof-auto

- -no-auto¶

Deprecated alias for

-fno-prof-auto

- -no-caf-all¶

Deprecated alias for

-fno-prof-cafs

8.4. Time and allocation profiling¶

To generate a time and allocation profile, give one of the following RTS

options to the compiled program when you run it (RTS options should be

enclosed between +RTS ... -RTS as usual):

- -p¶

- -P¶

- -pa¶

The

-poption produces a standard time profile report. It is written into the file<stem>.prof; the stem is taken to be the program name by default, but can be overridden by the-po ⟨stem⟩flag.The

-Poption produces a more detailed report containing the actual time and allocation data as well. (Not used much.)The

-paoption produces the most detailed report containing all cost centres in addition to the actual time and allocation data.

- -pj¶

The

-pjoption produces a time/allocation profile report in JSON format written into the file<program>.prof.

- -po ⟨stem⟩¶

The

-po ⟨stem⟩option overrides the stem used to form the output file paths for the cost-centre profiler (see-pand-pjflags above) and heap profiler (see-h).For instance, running a program with

+RTS -h -p -pohello-worldwould produce a heap profile namedhello-world.hpand a cost-centre profile namedhello-world.prof.

- -V ⟨secs⟩¶

- Default:

0.001 when profiling, and 0.01 otherwise

Sets the interval that the RTS clock ticks at, which is also the sampling interval of the time and allocation profile. The default is 0.001 seconds when profiling, and 0.01 otherwise. The runtime uses a single timer signal to count ticks; this timer signal is used to control the context switch timer (Using Concurrent Haskell) and the heap profiling timer RTS options for heap profiling. Also, the time profiler uses the RTS timer signal directly to record time profiling samples.

Normally, setting the

-V ⟨secs⟩option directly is not necessary: the resolution of the RTS timer is adjusted automatically if a short interval is requested with the-C ⟨s⟩or-i ⟨secs⟩options. However, setting-V ⟨secs⟩is required in order to increase the resolution of the time profiler.Using a value of zero disables the RTS clock completely, and has the effect of disabling timers that depend on it: the context switch timer and the heap profiling timer. Context switches will still happen, but deterministically and at a rate much faster than normal. Disabling the interval timer is useful for debugging, because it eliminates a source of non-determinism at runtime.

- -xc¶

This option causes the runtime to print out the current cost-centre stack whenever an exception is raised. This can be particularly useful for debugging the location of exceptions, such as the notorious

Prelude.head: empty listerror. See RTS options for Haskell program coverage.

8.4.1. JSON profile format¶

profile in a machine-readable JSON format. The JSON file can be directly loaded into speedscope.app to interactively view the profile.

The top-level object of this format has the following properties,

program(string)The name of the program

arguments(list of strings)The command line arguments passed to the program

rts_arguments(list of strings)The command line arguments passed to the runtime system

initial_capabilities(integral number)How many capabilities the program was started with (e.g. using the

-N ⟨x⟩option). Note that the number of capabilities may change during execution due to thesetNumCapabilitiesfunction.total_time(number)The total wall time of the program’s execution in seconds.

total_ticks(integral number)How many profiler “ticks” elapsed over the course of the program’s execution.

end_time(number)The approximate time when the program finished execution as a UNIX epoch timestamp.

tick_interval(float)How much time between profiler ticks.

total_alloc(integer)The cumulative allocations of the program in bytes.

cost_centres(list of objects)A list of the program’s cost centres

profile(object)The profile tree itself

Each entry in cost_centres is an object describing a cost-centre of the

program having the following properties,

id(integral number)A unique identifier used to refer to the cost-centre

is_caf(boolean)Whether the cost-centre is a Constant Applicative Form (CAF)

label(string)A descriptive string roughly identifying the cost-centre.

src_loc(string)A string describing the source span enclosing the cost-centre.

The profile data itself is described by the profile field, which contains a

tree-like object (which we’ll call a “cost-centre stack” here) with the

following properties,

id(integral number)The

idof a cost-centre listed in thecost_centreslist.entries(integral number)How many times was this cost-centre entered?

ticks(integral number)How many ticks was the program’s execution inside of this cost-centre? This does not include child cost-centres.

alloc(integral number)How many bytes did the program allocate while inside of this cost-centre? This does not include allocations while in child cost-centres.

children(list)A list containing child cost-centre stacks.

For instance, a simple profile might look like this,

{

"program": "Main",

"arguments": [

"nofib/shootout/n-body/Main",

"50000"

],

"rts_arguments": [

"-pj",

"-hy"

],

"end_time": "Thu Feb 23 17:15 2017",

"initial_capabilities": 0,

"total_time": 1.7,

"total_ticks": 1700,

"tick_interval": 1000,

"total_alloc": 3770785728,

"cost_centres": [

{

"id": 168,

"label": "IDLE",

"module": "IDLE",

"src_loc": "<built-in>",

"is_caf": false

},

{

"id": 156,

"label": "CAF",

"module": "GHC.Integer.Logarithms.Internals",

"src_loc": "<entire-module>",

"is_caf": true

},

{

"id": 155,

"label": "CAF",

"module": "GHC.Integer.Logarithms",

"src_loc": "<entire-module>",

"is_caf": true

},

{

"id": 154,

"label": "CAF",

"module": "GHC.Event.Array",

"src_loc": "<entire-module>",

"is_caf": true

}

],

"profile": {

"id": 162,

"entries": 0,

"alloc": 688,

"ticks": 0,

"children": [

{

"id": 1,

"entries": 0,

"alloc": 208,

"ticks": 0,

"children": [

{

"id": 22,

"entries": 1,

"alloc": 80,

"ticks": 0,

"children": []

}

]

},

{

"id": 42,

"entries": 1,

"alloc": 1632,

"ticks": 0,

"children": []

}

]

}

}

8.4.2. Eventlog profile format¶

In addition to the .prof and .json formats the cost centre definitions

and samples are also emitted to the eventlog. The format

of the events is specified in the eventlog encodings section.

8.5. Profiling memory usage¶

In addition to profiling the time and allocation behaviour of your program, you can also generate a graph of its memory usage over time. This is useful for detecting the causes of space leaks, when your program holds on to more memory at run-time that it needs to. Space leaks lead to slower execution due to heavy garbage collector activity, and may even cause the program to run out of memory altogether.

Heap profiling differs from time profiling in the fact that is not always

necessary to use the profiling runtime to generate a heap profile. There

are two heap profiling modes (-hT and -hi [1]) which are always

available.

To generate a heap profile from your program:

Assuming you need the profiling runtime, compile the program for profiling (Compiler options for profiling).

Run it with one of the heap profiling options described below (eg.

-hcfor a basic producer profile) and enable the eventlog using-l.Heap samples will be emitted to the GHC event log (see Heap profiler event log output for details about event format).

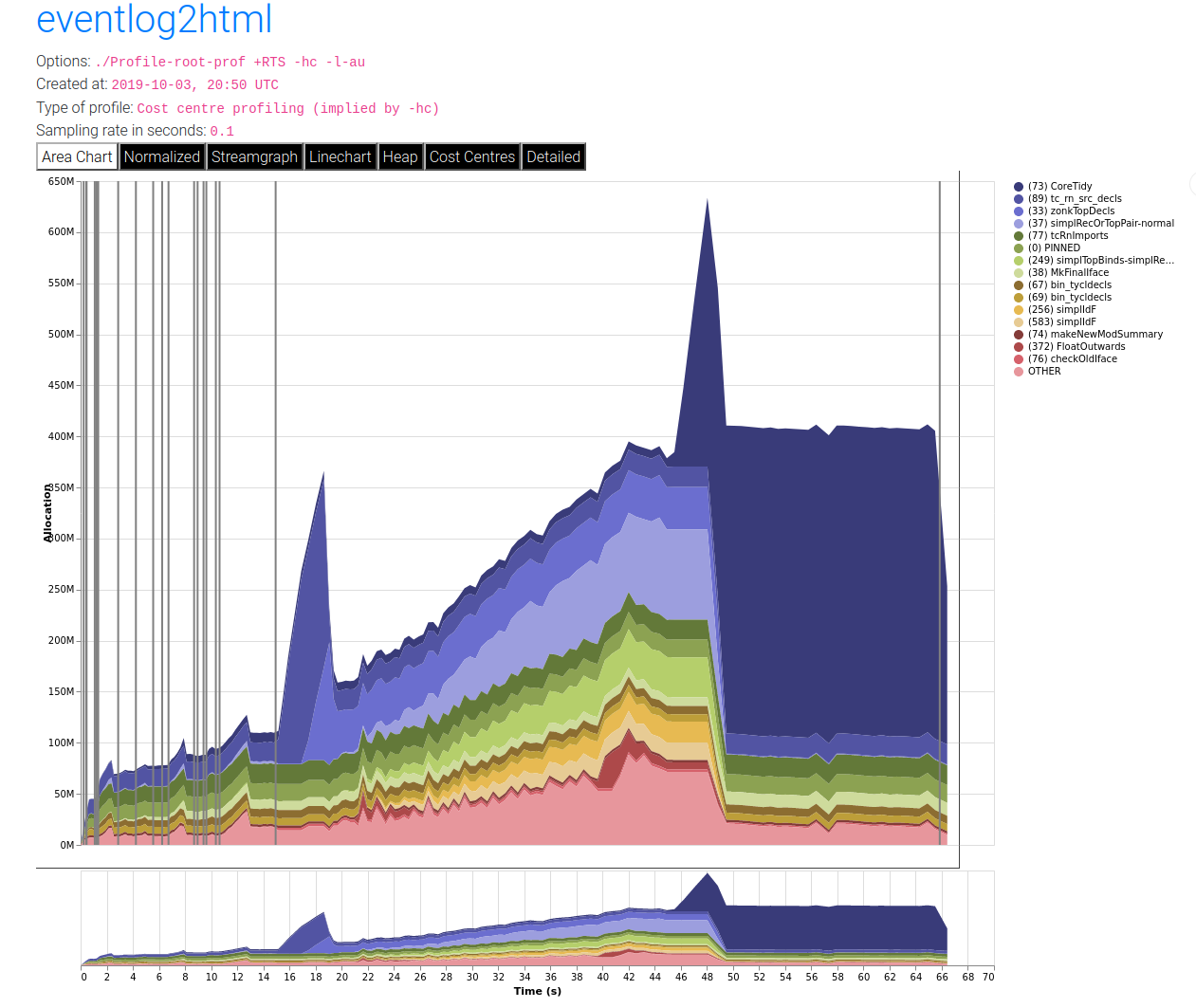

Render the heap profile using eventlog2html. This produces an HTML file which contains the visualised profile.

Open the rendered interactive profile in your web browser.

For example, here is a heap profile produced of using eventlog profiling on GHC compiling the Cabal library. You can read a lot more about eventlog2html on the website.

Note that there is the legacy prog.hp format which has been deprecated

in favour of eventlog based profiling. In order to render the legacy format, the

steps are as follows.

Run hp2ps to produce a Postscript file,

prog.ps. The hp2ps utility is described in detail in hp2ps – Rendering heap profiles to PostScript.Display the heap profile using a postscript viewer such as Ghostview, or print it out on a Postscript-capable printer.

For example, here is a heap profile produced for the sphere program

from GHC’s nofib benchmark suite,

Note that there might be a big difference between the OS reported memory usage of your program and the amount of live data as reported by heap profiling. The reasons for the difference are explained in Understanding how OS memory usage corresponds to live data.

8.5.1. RTS options for heap profiling¶

There are several different kinds of heap profile that can be generated. All the different profile types yield a graph of live heap against time, but they differ in how the live heap is broken down into bands. The following RTS options select which break-down to use:

- -hT¶

Breaks down the graph by heap closure type. This does not require the profiling runtime.

- -hm¶

Requires

-prof. Break down the live heap by the module containing the code which produced the data.

- -hd¶

Requires

-prof. Breaks down the graph by closure description. For actual data, the description is just the constructor name, for other closures it is a compiler-generated string identifying the closure.

- -hy¶

Requires

-prof. Breaks down the graph by type. For closures which have function type or unknown/polymorphic type, the string will represent an approximation to the actual type.

- -he¶

- Since:

9.10.1

Requires

-prof. Break down the graph by era.Each closure is tagged with the era in which it is created. Eras start at 1 and can be set in your program to domain specific values using functions from

GHC.Profiling.Erasor incremented automatically by the--automatic-era-increment.

- -hr¶

Requires

-prof. Break down the graph by retainer set. Retainer profiling is described in more detail below (Retainer Profiling).

- -hb¶

Requires

-prof. Break down the graph by biography. Biographical profiling is described in more detail below (Biographical Profiling).

- -hi¶

Break down the graph by the address of the info table of a closure. For this to produce useful output the program must have been compiled with

-finfo-table-mapbut it does not require the profiling runtime.

- -l

Emit profile samples to the GHC event log. This format is both more expressive than the old

.hpformat and can be correlated with other events over the program’s runtime. See Heap profiler event log output for details on the produced event structure.

In addition, the profile can be restricted to heap data which satisfies certain criteria - for example, you might want to display a profile by type but only for data produced by a certain module, or a profile by retainer for a certain type of data. Restrictions are specified as follows:

- -hc ⟨name⟩

Requires

-prof. Restrict the profile to closures produced by cost-centre stacks with one of the specified cost centres at the top.

- -hC ⟨name⟩

Requires

-prof. Restrict the profile to closures produced by cost-centre stacks with one of the specified cost centres anywhere in the stack.

- -hm ⟨module⟩

Requires

-prof. Restrict the profile to closures produced by the specified modules.

- -hd ⟨desc⟩

Requires

-prof. Restrict the profile to closures with the specified description strings.

- -hy ⟨type⟩

Requires

-prof. Restrict the profile to closures with the specified types.

- -he ⟨era⟩

Requires

-prof. Restrict the profile to the specified era.

- -hr ⟨cc⟩

Requires

-prof. Restrict the profile to closures with retainer sets containing cost-centre stacks with one of the specified cost centres at the top.

- -hb ⟨bio⟩

Requires

-prof. Restrict the profile to closures with one of the specified biographies, where ⟨bio⟩ is one oflag,drag,void, oruse.

For example, the following options will generate a retainer profile

restricted to Branch and Leaf constructors:

prog +RTS -hr -hdBranch,Leaf

There can only be one “break-down” option (eg. -hr in the example

above), but there is no limit on the number of further restrictions that

may be applied. All the options may be combined, with one exception: GHC

doesn’t currently support mixing the -hr and -hb options.

There are three more options which relate to heap profiling:

- -i ⟨secs⟩¶

Set the profiling (sampling) interval to ⟨secs⟩ seconds (the default is 0.1 second). Fractions are allowed: for example

-i0.2will get 5 samples per second. This only affects heap profiling; time profiles are always sampled with the frequency of the RTS clock. See Time and allocation profiling for changing that.

- --no-automatic-heap-samples¶

- Since:

9.2.1

Don’t start heap profiling from the start of program execution. If this option is enabled, it’s expected that the user will manually start heap profiling or request specific samples using functions from

GHC.Profiling.

- --no-automatic-time-samples¶

- Since:

9.10.1

Don’t start time profiling from the start of program execution. If this option is enabled, it’s expected that the user will manually start time profiling or request specific samples using functions from

GHC.Profiling.

- --automatic-era-increment¶

- Since:

9.10.1

Increment the era by 1 on each major garbage collection. This is used in conjunction with

-he.

- --null-eventlog-writer¶

- Since:

9.2.2

Don’t output eventlog to file, only configure tracing events. Meant to be used with customized event log writer.

- -L ⟨num⟩¶

Sets the maximum length of a cost-centre stack name in a heap profile. Defaults to 25.

8.5.2. Retainer Profiling¶

Retainer profiling is designed to help answer questions like “why is this data being retained?”. We start by defining what we mean by a retainer:

A retainer is either the system stack, an unevaluated closure (thunk), or an explicitly mutable object.

In particular, constructors are not retainers.

An object B retains object A if (i) B is a retainer object and (ii)

object A can be reached by recursively following pointers starting from

object B, but not meeting any other retainer objects on the way. Each

live object is retained by one or more retainer objects, collectively

called its retainer set, or its retainer set, or its retainers.

When retainer profiling is requested by giving the program the -hr

option, a graph is generated which is broken down by retainer set. A

retainer set is displayed as a set of cost-centre stacks; because this

is usually too large to fit on the profile graph, each retainer set is

numbered and shown abbreviated on the graph along with its number, and

the full list of retainer sets is dumped into the file prog.prof.

Retainer profiling requires multiple passes over the live heap in order

to discover the full retainer set for each object, which can be quite

slow. So we set a limit on the maximum size of a retainer set, where all

retainer sets larger than the maximum retainer set size are replaced by

the special set MANY. The maximum set size defaults to 8 and can be

altered with the -R ⟨size⟩ RTS option:

- -R ⟨size⟩¶

Restrict the number of elements in a retainer set to ⟨size⟩ (default 8).

8.5.2.1. Hints for using retainer profiling¶

The definition of retainers is designed to reflect a common cause of

space leaks: a large structure is retained by an unevaluated

computation, and will be released once the computation is forced. A good

example is looking up a value in a finite map, where unless the lookup

is forced in a timely manner the unevaluated lookup will cause the whole

mapping to be retained. These kind of space leaks can often be

eliminated by forcing the relevant computations to be performed eagerly,

using seq or strictness annotations on data constructor fields.

Often a particular data structure is being retained by a chain of

unevaluated closures, only the nearest of which will be reported by

retainer profiling - for example A retains B, B retains C, and

C retains a large structure. There might be a large number of Bs but

only a single A, so A is really the one we’re interested in eliminating.

However, retainer profiling will in this case report B as the retainer of

the large structure. To move further up the chain of retainers, we can ask for

another retainer profile but this time restrict the profile to B objects, so

we get a profile of the retainers of B:

prog +RTS -hr -hcB

This trick isn’t foolproof, because there might be other B closures in

the heap which aren’t the retainers we are interested in, but we’ve

found this to be a useful technique in most cases.

8.5.3. Precise Retainer Analysis¶

If you want to precisely answer questions about why a certain type of closure is retained then it is worthwhile using ghc-debug which has a terminal interface which can be used to easily answer queries such as, what is retaining a certain closure.

8.5.4. Biographical Profiling¶

A typical heap object may be in one of the following four states at each point in its lifetime:

The lag stage, which is the time between creation and the first use of the object,

the use stage, which lasts from the first use until the last use of the object, and

The drag stage, which lasts from the final use until the last reference to the object is dropped.

An object which is never used is said to be in the void state for its whole lifetime.

A biographical heap profile displays the portion of the live heap in each of the four states listed above. Usually the most interesting states are the void and drag states: live heap in these states is more likely to be wasted space than heap in the lag or use states.

It is also possible to break down the heap in one or more of these states by a different criteria, by restricting a profile by biography. For example, to show the portion of the heap in the drag or void state by producer:

prog +RTS -hc -hbdrag,void

Once you know the producer or the type of the heap in the drag or void states, the next step is usually to find the retainer(s):

prog +RTS -hr -hccc...

Note

This two stage process is required because GHC cannot currently profile using both biographical and retainer information simultaneously.

8.5.5. Actual memory residency¶

How does the heap residency reported by the heap profiler relate to the

actual memory residency of your program when you run it? You might see a

large discrepancy between the residency reported by the heap profiler,

and the residency reported by tools on your system (eg. ps or

top on Unix, or the Task Manager on Windows). There are several

reasons for this:

There is an overhead of profiling itself, which is subtracted from the residency figures by the profiler. This overhead goes away when compiling without profiling support, of course. The space overhead is currently 2 extra words per heap object, which probably results in about a 30% overhead.

Garbage collection requires more memory than the actual residency. The factor depends on the kind of garbage collection algorithm in use: a major GC in the standard generation copying collector will usually require \(3L\) bytes of memory, where \(L\) is the amount of live data. This is because by default (see the RTS

-F ⟨factor⟩option) we allow the old generation to grow to twice its size (\(2L\)) before collecting it, and we require additionally \(L\) bytes to copy the live data into. When using compacting collection (see the-coption), this is reduced to \(2L\), and can further be reduced by tweaking the-F ⟨factor⟩option. Also add the size of the allocation area (see-A ⟨size⟩).The program text itself, the C stack, any non-heap data (e.g. data allocated by foreign libraries, and data allocated by the RTS), and

mmap()'d memory are not counted in the heap profile.

For more discussion about understanding how understanding process residency see Understanding how OS memory usage corresponds to live data.

8.6. hp2ps – Rendering heap profiles to PostScript¶

Usage:

hp2ps [flags] [<file>[.hp]]

The program hp2ps program converts a .hp file produced

by the -h<break-down> runtime option into a PostScript graph of the

heap profile. By convention, the file to be processed by hp2ps has a

.hp extension. The PostScript output is written to file@.ps.

If <file> is omitted entirely, then the program behaves as a filter.

hp2ps is distributed in ghc/utils/hp2ps in a GHC source

distribution. It was originally developed by Dave Wakeling as part of

the HBC/LML heap profiler.

The flags are:

- -d¶

In order to make graphs more readable,

hp2pssorts the shaded bands for each identifier. The default sort ordering is for the bands with the largest area to be stacked on top of the smaller ones. The-doption causes rougher bands (those representing series of values with the largest standard deviations) to be stacked on top of smoother ones.

- -b¶

Normally,

hp2psputs the title of the graph in a small box at the top of the page. However, if the JOB string is too long to fit in a small box (more than 35 characters), thenhp2pswill choose to use a big box instead. The-boption forceshp2psto use a big box.

- -e⟨float⟩[in|mm|pt]¶

Generate encapsulated PostScript suitable for inclusion in LaTeX documents. Usually, the PostScript graph is drawn in landscape mode in an area 9 inches wide by 6 inches high, and

hp2psarranges for this area to be approximately centred on a sheet of a4 paper. This format is convenient of studying the graph in detail, but it is unsuitable for inclusion in LaTeX documents. The-eoption causes the graph to be drawn in portrait mode, with float specifying the width in inches, millimetres or points (the default). The resulting PostScript file conforms to the Encapsulated PostScript (EPS) convention, and it can be included in a LaTeX document using Rokicki’s dvi-to-PostScript converterdvips.

- -g¶

Create output suitable for the

gsPostScript previewer (or similar). In this case the graph is printed in portrait mode without scaling. The output is unsuitable for a laser printer.

- -l¶

Normally a profile is limited to 20 bands with additional identifiers being grouped into an

OTHERband. The-lflag removes this 20 band and limit, producing as many bands as necessary. No key is produced as it won’t fit!. It is useful for creation time profiles with many bands.

- -m⟨int⟩¶

Normally a profile is limited to 20 bands with additional identifiers being grouped into an

OTHERband. The-mflag specifies an alternative band limit (the maximum is 20).-m0requests the band limit to be removed. As many bands as necessary are produced. However no key is produced as it won’t fit! It is useful for displaying creation time profiles with many bands.

- -p¶

Use previous parameters. By default, the PostScript graph is automatically scaled both horizontally and vertically so that it fills the page. However, when preparing a series of graphs for use in a presentation, it is often useful to draw a new graph using the same scale, shading and ordering as a previous one. The

-pflag causes the graph to be drawn using the parameters determined by a previous run ofhp2psonfile. These are extracted fromfile@.aux.

- -s¶

Use a small box for the title.

- -t⟨float⟩¶

Normally trace elements which sum to a total of less than 1% of the profile are removed from the profile. The

-toption allows this percentage to be modified (maximum 5%).-t0requests no trace elements to be removed from the profile, ensuring that all the data will be displayed.

- -c¶

Generate colour output.

- -y¶

Ignore marks.

- -?¶

Print out usage information.

8.7. Profiling Parallel and Concurrent Programs¶

Combining -threaded and -prof is perfectly fine, and

indeed it is possible to profile a program running on multiple processors with

the RTS -N ⟨x⟩ option. [3]

Some caveats apply, however. In the current implementation, a profiled program is likely to scale much less well than the unprofiled program, because the profiling implementation uses some shared data structures which require locking in the runtime system. Furthermore, the memory allocation statistics collected by the profiled program are stored in shared memory but not locked (for speed), which means that these figures might be inaccurate for parallel programs.

We strongly recommend that you use -fno-prof-count-entries when

compiling a program to be profiled on multiple cores, because the entry

counts are also stored in shared memory, and continuously updating them

on multiple cores is extremely slow.

We also recommend using ThreadScope for profiling parallel programs; it offers a GUI for visualising parallel execution, and is complementary to the time and space profiling features provided with GHC.

8.8. Observing Code Coverage¶

Code coverage tools allow a programmer to determine what parts of their code have been actually executed, and which parts have never actually been invoked. GHC has an option for generating instrumented code that records code coverage as part of the Haskell Program Coverage (HPC) toolkit, which is included with GHC. HPC tools can be used to render the generated code coverage information into human understandable format.

Correctly instrumented code provides coverage information of two kinds: source coverage and boolean-control coverage. Source coverage is the extent to which every part of the program was used, measured at three different levels: declarations (both top-level and local), alternatives (among several equations or case branches) and expressions (at every level). Boolean coverage is the extent to which each of the values True and False is obtained in every syntactic boolean context (ie. guard, condition, qualifier).

HPC displays both kinds of information in two primary ways: textual

reports with summary statistics (hpc report) and sources with color

mark-up (hpc markup). For boolean coverage, there are four possible

outcomes for each guard, condition or qualifier: both True and False

values occur; only True; only False; never evaluated. In hpc-markup

output, highlighting with a yellow background indicates a part of the

program that was never evaluated; a green background indicates an

always-True expression and a red background indicates an always-False

one.

8.8.1. A small example: Reciprocation¶

For an example we have a program, called Recip.hs, which computes

exact decimal representations of reciprocals, with recurring parts

indicated in brackets.

reciprocal :: Int -> (String, Int)

reciprocal n | n > 1 = ('0' : '.' : digits, recur)

| otherwise = error

"attempting to compute reciprocal of number <= 1"

where

(digits, recur) = divide n 1 []

divide :: Int -> Int -> [Int] -> (String, Int)

divide n c cs | c `elem` cs = ([], position c cs)

| r == 0 = (show q, 0)

| r /= 0 = (show q ++ digits, recur)

where

(q, r) = (c*10) `quotRem` n

(digits, recur) = divide n r (c:cs)

position :: Int -> [Int] -> Int

position n (x:xs) | n==x = 1

| otherwise = 1 + position n xs

showRecip :: Int -> String

showRecip n =

"1/" ++ show n ++ " = " ++

if r==0 then d else take p d ++ "(" ++ drop p d ++ ")"

where

p = length d - r

(d, r) = reciprocal n

main = do

number <- readLn

putStrLn (showRecip number)

main

HPC instrumentation is enabled with the -fhpc flag:

$ ghc -fhpc Recip.hs

GHC creates a subdirectory .hpc in the current directory, and puts

HPC index (.mix) files in there, one for each module compiled. You

don’t need to worry about these files: they contain information needed

by the hpc tool to generate the coverage data for compiled modules

after the program is run.

$ ./Recip

1/3

= 0.(3)

Running the program generates a file with the .tix suffix, in this

case Recip.tix, which contains the coverage data for this run of the

program. The program may be run multiple times (e.g. with different test

data), and the coverage data from the separate runs is accumulated in

the .tix file. To reset the coverage data and start again, just

remove the .tix file. You can control where the .tix file

is generated using the environment variable HPCTIXFILE.

- HPCTIXFILE¶

Set the HPC

.tixfile output path.

Having run the program, we can generate a textual summary of coverage:

$ hpc report Recip

80% expressions used (81/101)

12% boolean coverage (1/8)

14% guards (1/7), 3 always True,

1 always False,

2 unevaluated

0% 'if' conditions (0/1), 1 always False

100% qualifiers (0/0)

55% alternatives used (5/9)

100% local declarations used (9/9)

100% top-level declarations used (5/5)

We can also generate a marked-up version of the source.

$ hpc markup Recip

writing Recip.hs.html

This generates one file per Haskell module, and 4 index files,

hpc_index.html, hpc_index_alt.html, hpc_index_exp.html,

hpc_index_fun.html.

8.8.2. Options for instrumenting code for coverage¶

- -fhpc¶

Enable code coverage for the current module or modules being compiled.

Modules compiled with this option can be freely mixed with modules compiled without it; indeed, most libraries will typically be compiled without

-fhpc. When the program is run, coverage data will only be generated for those modules that were compiled with-fhpc, and the hpc tool will only show information about those modules.

- -hpcdir⟨dir⟩¶

- Default:

.hpc

Override the directory where GHC places the HPC index (

.mix) files used byhpcto understand program structure.

8.8.3. The hpc toolkit¶

The hpc command has several sub-commands:

$ hpc

Usage: hpc COMMAND ...

Commands:

help Display help for hpc or a single command

Reporting Coverage:

report Output textual report about program coverage

markup Markup Haskell source with program coverage

Processing Coverage files:

sum Sum multiple .tix files in a single .tix file

combine Combine two .tix files in a single .tix file

map Map a function over a single .tix file

Coverage Overlays:

overlay Generate a .tix file from an overlay file

draft Generate draft overlay that provides 100% coverage

Others:

show Show .tix file in readable, verbose format

version Display version for hpc

In general, these options act on a .tix file after an instrumented

binary has generated it.

The hpc tool assumes you are in the top-level directory of the location

where you built your application, and the .tix file is in the same

top-level directory. You can use the flag --srcdir to use hpc

for any other directory, and use --srcdir multiple times to analyse

programs compiled from difference locations, as is typical for packages.

We now explain in more details the major modes of hpc.

8.8.3.1. hpc report¶

hpc report gives a textual report of coverage. By default, all

modules and packages are considered in generating report, unless include

or exclude are used. The report is a summary unless the --per-module

flag is used. The --xml-output option allows for tools to use hpc to

glean coverage.

$ hpc help report

Usage: hpc report [OPTION] .. <TIX_FILE> [<MODULE> [<MODULE> ..]]

Options:

--per-module show module level detail

--decl-list show unused decls

--exclude=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] exclude MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--include=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] include MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--srcdir=DIR path to source directory of .hs files

multi-use of srcdir possible

--hpcdir=DIR append sub-directory that contains .mix files

default .hpc [rarely used]

--reset-hpcdirs empty the list of hpcdir's

[rarely used]

--xml-output show output in XML

8.8.3.2. hpc markup¶

hpc markup marks up source files into colored html.

$ hpc help markup

Usage: hpc markup [OPTION] .. <TIX_FILE> [<MODULE> [<MODULE> ..]]

Options:

--exclude=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] exclude MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--include=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] include MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--srcdir=DIR path to source directory of .hs files

multi-use of srcdir possible

--hpcdir=DIR append sub-directory that contains .mix files

default .hpc [rarely used]

--reset-hpcdirs empty the list of hpcdir's

[rarely used]

--fun-entry-count show top-level function entry counts

--highlight-covered highlight covered code, rather that code gaps

--destdir=DIR path to write output to

8.8.3.3. hpc sum¶

hpc sum adds together any number of .tix files into a single

.tix file. hpc sum does not change the original .tix file;

it generates a new .tix file.

$ hpc help sum

Usage: hpc sum [OPTION] .. <TIX_FILE> [<TIX_FILE> [<TIX_FILE> ..]]

Sum multiple .tix files in a single .tix file

Options:

--exclude=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] exclude MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--include=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] include MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--output=FILE output FILE

--union use the union of the module namespace (default is intersection)

8.8.3.4. hpc combine¶

hpc combine is the swiss army knife of hpc. It can be used to

take the difference between .tix files, to subtract one .tix

file from another, or to add two .tix files. hpc combine does not

change the original .tix file; it generates a new .tix file.

$ hpc help combine

Usage: hpc combine [OPTION] .. <TIX_FILE> <TIX_FILE>

Combine two .tix files in a single .tix file

Options:

--exclude=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] exclude MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--include=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] include MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--output=FILE output FILE

--function=FUNCTION combine .tix files with join function, default = ADD

FUNCTION = ADD | DIFF | SUB

--union use the union of the module namespace (default is intersection)

8.8.3.5. hpc map¶

hpc map inverts or zeros a .tix file. hpc map does not change the

original .tix file; it generates a new .tix file.

$ hpc help map

Usage: hpc map [OPTION] .. <TIX_FILE>

Map a function over a single .tix file

Options:

--exclude=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] exclude MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--include=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] include MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--output=FILE output FILE

--function=FUNCTION apply function to .tix files, default = ID

FUNCTION = ID | INV | ZERO

--union use the union of the module namespace (default is intersection)

8.8.3.6. hpc overlay and hpc draft¶

Overlays are an experimental feature of HPC, a textual description of coverage. hpc draft is used to generate a draft overlay from a .tix file, and hpc overlay generates a .tix files from an overlay.

% hpc help overlay

Usage: hpc overlay [OPTION] .. <OVERLAY_FILE> [<OVERLAY_FILE> [...]]

Options:

--srcdir=DIR path to source directory of .hs files

multi-use of srcdir possible

--hpcdir=DIR append sub-directory that contains .mix files

default .hpc [rarely used]

--reset-hpcdirs empty the list of hpcdir's

[rarely used]

--output=FILE output FILE

% hpc help draft

Usage: hpc draft [OPTION] .. <TIX_FILE>

Options:

--exclude=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] exclude MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--include=[PACKAGE:][MODULE] include MODULE and/or PACKAGE

--srcdir=DIR path to source directory of .hs files

multi-use of srcdir possible

--hpcdir=DIR append sub-directory that contains .mix files

default .hpc [rarely used]

--reset-hpcdirs empty the list of hpcdir's

[rarely used]

--output=FILE output FILE

8.8.4. Caveats and Shortcomings of Haskell Program Coverage¶

HPC does not attempt to lock the .tix file, so multiple concurrently

running binaries in the same directory will exhibit a race condition.

At compile time, there is no way to change the name of the .tix file generated;

at runtime, the name of the generated .tix file can be changed

using HPCTIXFILE; the name of the .tix file

will also change if you rename the binary. HPC does not work with GHCi.

8.9. Using “ticky-ticky” profiling (for implementors)¶

- -ticky¶

Enable ticky-ticky profiling. By default this only tracks the allocations by each closure type. See

-ticky-allocdto keep track of allocations of each closure type as well.

GHC’s ticky-ticky profiler provides a low-level facility for tracking entry and allocation counts of particular individual closures. Ticky-ticky profiling requires a certain familiarity with GHC internals, so it is best suited for expert users, but can provide an invaluable precise insight into the allocation behaviour of your programs.

Getting started with ticky profiling consists of three steps.

Add the

-tickyflag when compiling a Haskell module to enable “ticky-ticky” profiling of that module. This makes GHC emit performance-counting instructions in every STG function.Add

-tickyto the command line when linking, so that you link against a version of the runtime system that allows you to display the results. In fact, in the link phase -ticky implies -debug, so you get the debug version of the runtime system too.Then when running your program you can collect the results of the profiling in two ways.

Using the eventlog, the

-lTflag will emit ticky samples to the eventlog periodically. This has the advantage of being able to resolve dynamic behaviors over the program’s lifetime. See Ticky counters for details on the event types reported. The ticky information can be rendered into an interactive table using eventlog2html.A legacy textual format is emitted using the

-r ⟨file⟩flag. This produces a textual table containing information about how much each counter ticked throughout the duration of the program.

8.9.1. Additional Ticky Flags¶

There are some additional flags which can be used to increase the number of ticky counters and the quality of the profile.

- -ticky-allocd¶

Keep track of how much each closure type is allocated.

- -ticky-dyn-thunk¶

Track allocations of dynamic thunks.

- -ticky-LNE¶

These are not allocated, and can be very performance sensitive so we usually don’t want to run ticky counters for these to avoid even worse performance for tickied builds.

But sometimes having information about these binders is critical. So we have a flag to ticky them anyway.

- -ticky-tag-checks¶

These dummy counters contain:

The number of avoided tag checks in the entry count.

“infer” as the argument string to distinguish them from regular counters.

The name of the variable we are casing on, as well as a unique to represent the inspection site as one variable might be cased on multiple times. The unique comes first with the variable coming at the end. Like this:

u10_s98c (Main) at nofib/spectral/simple/Main.hs:677:1 in u10where u10 is the variable and u10_s98c the unique associated with the inspection site.

Note that these counters are currently not processed well be eventlog2html. So if you want to check them you will have to use the text based interface.

- -ticky-ap-thunk¶

This allows us to get accurate entry counters for code like f x y at the cost of code size. We do this but not using the precomputed standard AP thunk code.

GHC’s ticky-ticky profiler provides a low-level facility for tracking entry and allocation counts of particular individual closures. Because ticky-ticky profiling requires a certain familiarity with GHC internals, we have moved the documentation to the GHC developers wiki. Take a look at its overview of the profiling options, which includes a link to the ticky-ticky profiling page.

Note that ticky-ticky samples can be emitted in two formats: the eventlog,

using the -lT event type, and a plain text

summary format, using the -r ⟨file⟩ option. The former has the

advantage of being able to resolve dynamic behaviors over the program’s

lifetime. See Ticky counters for details on the event types

reported.

8.9.2. Understanding the Output of Ticky-Ticky profiles¶

Once you have your rendered profile then you can begin to understand the allocation behaviour of your program. There are two classes of ticky-ticky counters.

Name-specific counters

Each “name-specific counter” is associated with a name that is defined in the result of the optimiser. For each such name, there are three possible counters: entries, heap allocation by the named thing, and heap used to allocate that named thing.

Global counters

Each “global counter” describes some aspect of the entire program execution. For example, one global counter tracks total heap allocation; another tracks allocation for PAPs.

In general you are probably interested mostly in the name-specific counters as these can provided detailed information about where allocates how much in your program.

8.9.3. Information about name-specific counters¶

Name-specific counters provide the following information about a closure.

Entries - How many times the closure was entered.

Allocs - How much (in bytes) is allocated by that closure.

Allod - How often the closure is allocated.

FVs - The free variables captured by that closure.

Args - The arguments that closure takes.

The FVs and Args information is encoded using a small DSL.

Classification |

Description |

|---|---|

|

dictionary |

|

function |

|

char, int, float, double, word |

|

unboxed ditto |

|

unboxed tuple |

|

other primitive type |

|

unboxed primitive type |

|

list |

|

enumeration type |

|

single-constructor type |

|

multi-constructor type |

|

other type |

|

reserved for others to mark as “uninteresting” |

In particular note that you can use the ticky profiler to see any function

calls to dictionary arguments by searching the profile for the + classifier.

This indicates that the function has failed to specialise for one reason or another.

8.9.4. Examples¶

A typical use of ticky-ticky would be to generate a ticky report using the eventlog by evoking an application with RTS arguments like this:

app <args> +RTS -l-augT

This will produce an eventlog file which contains results from ticky counters. This file can be manually inspected like any regular eventlog. However for ticky-ticky eventlog2html has good support for producing tables from these logs.

With an up to date version of eventlog2html this can be simply done by invoking eventlog2html

on the produced eventlog. In the example above the invocation would then be eventlog2html app.eventlog

Which will produce a searchable and sortable table containing all the ticky counters in the log.

8.9.5. Notes about ticky profiling¶

You can mix together modules compiled with and without

-tickybut you will miss out on allocations and counts from uninstrumented modules in the profile.Linking with the

-tickyhas a quite severe performance impact on your program.-tickyimplies using the unoptimised-debugRTS. Therefore-tickyshouldn’t be used for production builds.Building with

-tickydoesn’t affect core optimisations of your program as the counters are inserted after the STG pipeline. At which point most optimizations have already been run.When using the eventlog it is possible to combine together ticky-ticky and IPE based profiling as each ticky counter definition has an associated info table. This address can be looked up in the IPE map so that further information (such as source location) can be determined about that closure.

Global ticky counters are only available in the textual ticky output (

+RTS -r). But this mode has some limitations (e.g. on column widths) and will contain raw json output in some columns. For this reason using an eventlog-based approach should be prefered if possible.